An introduction to memory models

In this series of posts we will visit the concept of memory models using “real-world” examples. We will look behind the scenes and into a programming language’s implementation. We will see how the specification of the memory model relates to the language’s implementation.

Below we cover some basics: what is a memory model and why do these models matter. We will touch on concepts associated with multi-threading and synchronization, such as the concept of sequential consistency, weak- or relaxed-memory, atomicity, etc. In future posts, we will discuss the Golang memory model and we will look into Go runtime source code. But first, a confession.

My background is in engineering, not in computer science, and I managed to have a fine career in Silicon Valley without having to think too hard about the concept of a memory model. For the better part of my tenure, I wasn’t even fully aware of the concept. I knew quite a bit about caches, paging and virtual memory management, hardware pipelines, etc, but the connection between hardware and programming-language concepts was still a bit fuzzy for me.

Now, at the course of my graduate studies, I’ve had the opportunity to lecture about memory models at the university. In these lectures, I talk about hardware’s take on memory (low level), about software’s guarantees to the programmer (high level), about how a language’s memory model forms a contract between these two levels of abstraction, and about the role of a compiler in all of this.

This post is, in part, based on one of those lectures.

My background is in engineering, not in computer science, and I managed to have a fine career in Silicon Valley without having to think too hard about the concept of a memory model. For the better part of my tenure, I wasn’t even fully aware of the concept. I knew quite a bit about caches, paging and virtual memory management, hardware pipelines, etc, but the connection between hardware and programming-language concepts was still a bit fuzzy for me.

Now, at the course of my graduate studies, I’ve had the opportunity to lecture about memory models at the university. In these lectures, I talk about hardware’s take on memory (low level), about software’s guarantees to the programmer (high level), about how a language’s memory model forms a contract between these two levels of abstraction, and about the role of a compiler in all of this.

This post is, in part, based on one of those lectures.

Turns out memory models are quite interesting. And it amazes me how anything works given how complex and elusive memory can be. We will have plenty to talk about, even from the smallest examples. You may be surprised by how much we can unpack from just six lines of code or so.

Let’s start with this example here. What does this program do?

T1 | T2

z = 42 | if (done)

done = true | print(z)

There are two threads, T1 and T2, and they are trying to synchronize with each other. T1 does some work, represented here by the setting a shared variable z to 42. T2 checks if the work is done, and if so, it prints the value of the shared variable out.

The answer to “what does this program do” is: it depends.

T2 may execute before T1, in which case done is false and nothing is printed.

But even if T2 observes the value of done to be true it doesn’t mean it will print the value of 42. It is possible for T2 to print zero. If you are not so sure about why that’s the case, then read on…

A short primer on memory models

The question of “what does the above program do?” is settled by a memory model. So what exactly is a memory model? Let us look at what people have to say. Here is one way to describe it:

[A memory model is] a formal specification of how the memory system will appear to the programmer, eliminating the gap between the behavior expected by the programmer and the actual behavior supported by a system.

The quote comes from a famous and very clarifying research paper. But you probably don’t get a clear picture given this definition. So, let’s try again:

A memory model dictates what values a read from memory can return given previous writes to memory.

Wait a minute… if I read before writing, I should read some uninitialized or pre-initialized value. And if I read after writing, then I read what I wrote. What’s the catch? The catch is that the definition seems too trivial: it doesn’t talk about what’s actually interesting about memory models. The definition does not touch on concurrency.

If I have one agent reading and writing to memory, then a memory model is trivial: we read what we wrote. But what if many agents are writing to memory. What values can we observe then? That’s the question a memory model helps you answer.

Here is another definition, this time from the Go programming language:

The Go memory model specifies the conditions under which reads of a variable in one goroutine can be guaranteed to observe values produced by writes to the same variable in a different goroutine.

This is specific to Go, but it doesn’t have to be. We could just as easily replace “The Go memory model” by “A memory model”, and “goroutine” by “thread”:

A memory model specifies the conditions under which reads of a variable in one thread can be guaranteed to observe values produced by writes to the same variable in a different thread.

There we go. That’s a fine definition. It talks about reads observing writes and talks about what makes a memory model interesting: multiple agents interacting via shared memory.

The problem with memory models

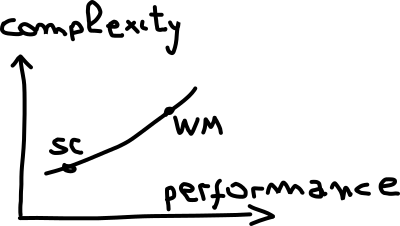

In computing, we often encounter a trade-off between performance and complexity, and it generally looks like this:

We want performance, but performance comes at a cost: increased complexity. The same trade-off happens with memory models. There isn’t one absolute memory model but many. At the bottom left we have sequential consistency (SC). Memory models that are sequentially consistent are easier to understand, but don’t yield very good performance. As we move to the right, we move towards what is called weak memory (WM). There are many flavors of weak memory models. These models differ based on the specifics of how they trade simplicity for performance.

But before we get ahead of ourselves, let us see what a sequentially consistent memory model looks like. The original definition from 1979 by Lamport says:

[A memory model is sequentially consistent when] the results of any execution is the same as if the operations of all the processors were executed in some sequential order, and the operations of each individual processor appear in this sequence in the order specified by its program.

Say what?!

Let us try again with another definition:

In a sequentially consistent model, memory acts as a shared global repository where operations appear atomic and in program order.

There are two concepts here: atomicity and program order.

Atomicity tells you that if two people try to write to the same location at the same time, the result will not be a mumble jumble with part of one write and part of another. Instead, one write will “win” by overwriting the other.

Program order is the order of instructions in the program text. The compiler is allowed some freedom rearranging instructions, and processors are also allowed some freedom in the order of execution of these instructions. However, when it comes sequentially consistent memory models, the rules are pretty strict. Instruction reordering can still happens. Sequential consistency says that the result must be as if instructions were executed in program order. The compiler or the hardware can still compile/execute instructions out-of-order, as long as we are not able to tell the difference.

Enough with definitions for now. Let us go back to our original example.

Closing the loop

Let us go back to our original example and label the program locations A, B, C, and D:

T1 | T2

z = 42 (A) | if (done) (C)

done = true (B) | print(z) (D)

In a sequentially consistent world, if T2 observes the value of done to be true, then it must be because T1 set it to true in B. Because instructions must appear to have been executed in program order, then it must be that T1 has already set z to 42 in A. Therefore, the print statement in D will necessarily print 42. Bingo! Our program is properly synchronized from the point of view of a sequentially consistent memory model.

Life is good and we can go home now. Well… except that most programming languages and processors are not sequentially consistent. In our ever quest for performance, we have designed compilers and processors to deviate from sequential consistency. These deviations are also called relaxations, as they relax the order of instructions and their execution. “Relaxed” and “weak” are used interchangeably. A relaxed memory model is a weak memory model.

Under weak memory, it is possible for the instructions in T1 to be swapped.

T1 | T2

done = true (B) | if (done) (C)

z = 42 (A) | print(z) (D)

The single-threaded behavior of T1 is still the same: both done and z get set to true and 42. However, the swap breaks the intent of the overall program. It is now possible for T2 to perceive done being true and for the print-statement to then print the uninitialized value of z.

How can we make sense of these swaps? We explore weak memory models further on the next post.